Riesz's Representation Theorem

Introduction

Riesz’s representation theorem is a powerful result in functional analysis, particularly in the study of Hilbert spaces. It characterizes continuous linear functionals in terms of the inner product. However, in this post, we don’t assume any inner product structure and only work on $\ell^p$, the standard sequence spaces.

Recall that the $\ell^p$ space is the space of (infinite) sequences

\[\ell^p=\left\{\left\{a_j\right\}_{j=1}^{\infty}:\|a\|_p<\infty\right\},\]where we define the $\ell^p$ norm

\[\|a\|_p= \begin{cases}\left(\sum_{j=1}^{\infty}\left|a_j\right|^p\right)^{1 / p} & 1 \leq p<\infty \\ \sup _{1 \leq j \leq \infty}\left|a_j\right| & p=\infty .\end{cases}\]Main theorems

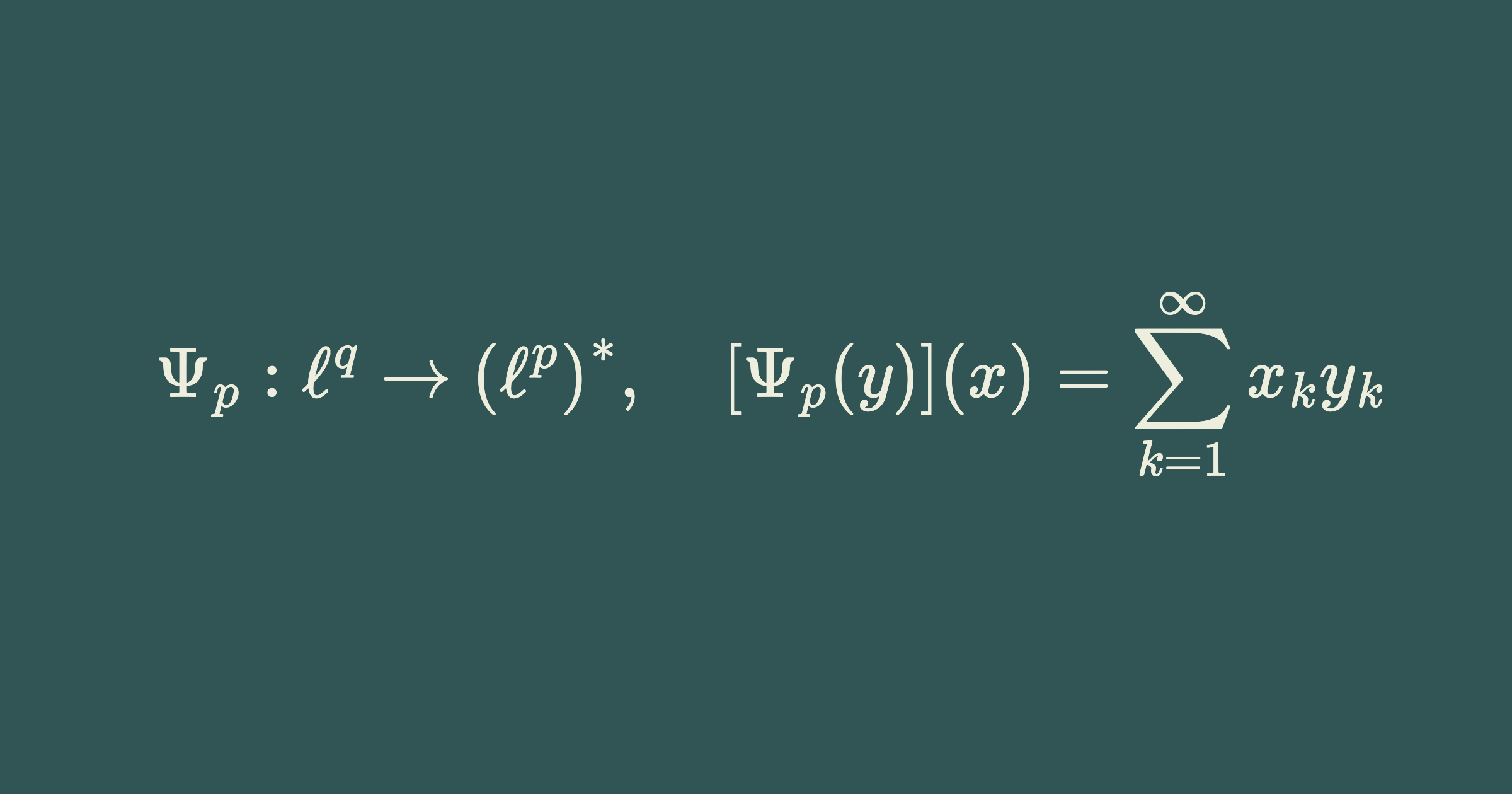

Theorem 1 (Riesz’s $\ell^p$ representation theorem $1 \leq p < \infty$) Let $p \in[1, \infty)$ and $q$ be the conjugate parameter of $p$. Define $\Psi_p: \ell^q \rightarrow\left(\ell^p\right)^*$ as

\[\left[\Psi_p(y)\right](x)=\sum_{k=1}^{\infty} x_k y_k .\]Then $\Psi_p$ is an isomorphism.

Recall that $A: X \rightarrow Y$ is an isomorphism if $A$ is linear, bijective, and norm preserving i.e. $||A x||_Y=||x||_X$ for all $x \in X$.

Proof: It is not clear that $\Psi_p$ is well defined at this point. Let us show that $\forall y \in \ell^q$, $\Psi_p(y) \in \left(\ell^p\right)^*$ i.e. $\Psi_p(y)$ is a linear bounded functional on $\ell^p$.

$\Psi_p(y)$ is linear:Let $x^{(1)}$, $x^{(2)} \in \ell^p$, $\alpha \in \mathbb{C}$, and $y \in \ell^q$. Then

\[\begin{align*} \left[\Psi_p(y)\right](\alpha x^{(1)} + x^{(2)}) &= \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} (\alpha x^{(1)}_k + x^{(2)}_k) y_k \overset{\text{sum rule and scalar product rule}}{=} \alpha \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} x_k^{(1)} y_k + \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} x_k^{(2)} y_k\\ &= \left[\Psi_p(y)\right](\alpha x^{(1)}) + \left[\Psi_p( y)\right](x^{(2)}). \end{align*}\] $\Psi_p$ is norm preserving:Let $y \in \ell^q$ and $x \in \ell^p$. By triangle inequality and Hölder’s inequality, we have

\[\left|\left[\Psi_p(y)\right](x)\right| \leq \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} |x_k y_k| \leq \|x\|_p\|y\|_q .\]So $|\Psi_p(y)| \leq || y ||_q$. Note that this shows that $\Psi_p(y)$ is bounded and $\Psi_p$ is well defined. To see that $|\Psi_p(y)|=||y||_q$, define the sequence $x$ as

\[x_k= \begin{cases} \left|y_k\right|^{q-1} \frac{\overline{y_k}}{\left|y_k\right|}, & y_k \neq 0,\\ 0, & y_k=0. \end{cases}\]Since $q$ and $p$ are conjugate parameters, we have $(q-1) p=q$. So $\forall k, \left|x_k\right|^p=\left|y_k\right|^q,||x||_p^p=||y||_q^q$ and $x \in \ell^p$. Furthermore,

\[\begin{aligned} \left|\Psi_p(y)(x)\right| & =\left|\sum_{k=1}^{\infty}\left|y_k\right|^{q-2} y_k \overline{y_k} \right| \\ & =\|y\|_q^q=\|y\|_q\|y\|_q^{q-1} \\ & =\|y\|_q^q\|x\|_p^{p\left(1-q^{-1}\right)}=\|y\|_q\|x\|_p. \end{aligned}\]So $|\Psi_p(y)|=||y||_q$. Note that if $\Psi_p$ is norm preserving, then $\Psi_p$ is bounded and injective (check this!).

$\Psi_p$ is linear:Let $y^{(1)}$, $y^{(2)} \in \ell^q$, $\alpha \in \mathbb{C}$, and $x \in \ell^p$. Then

\[\begin{align*} \left[\Psi_p(\alpha y^{(1)} + y^{(2)})\right](x) &= \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} x_k\left(\alpha y^{(1)}_k + y^{(2)}_k\right)\overset{\text{sum rule and scalar product rule}}{=} \alpha \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} x_k y^{(1)}_k + \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} x_k y^{(2)}_k\\ &= \left[\Psi_p(\alpha y^{(1)})\right](x) + \left[\Psi_p( y^{(2)})\right](x). \end{align*}\] $\Psi_p$ is surjective:Let us show $\forall \psi \in (\ell^p)^{*} ~ \exists y \in \ell^q$ such that $\Psi_p(y) = \psi$. Define the sequence $(e^{(n)}) \subset \mathbf{c}_{00}$ as

\[e_k^{(n)}= \begin{cases}1 & \text { if } n=k, \\ 0 & \text { otherwise. }\end{cases}\] Claim:$\forall x \in \ell^p$, we have

\[x=\sum_{k=1}^{\infty} x_k e^{(k)}.\] Proof of the claim:Let

\[x^{(n)}=\sum_{k=1}^n x_k e^{(k)}.\]Observe that

\[\left\|x-x^{(n)}\right\|_p^p \overset{\text{defn of vector `substraction'}}{=}\sum_{k=n+1}^{\infty}\left|x_k\right|^p \rightarrow 0\]since the tail of a convergent series vanishes. So $x^{(n)} \to x$ as claimed. ◼

For $\psi \in\left(\ell^p\right)^*$, define the sequence $y$ as $y_k=\psi \left(e^{(k)}\right)$. We can see that if $y \in \ell^q$, then $\forall x \in \ell^p$,

\[\begin{align*} \psi(x) &= \psi \left(\lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{k=1}^{n} x^{(n)}\right) \overset{\psi \text{ is bounded }}{=} \lim_{n \to \infty}\psi \left(\sum_{k=1}^{n} x^{(n)}\right) \overset{\psi \text{ is linear }}{=} \lim_{n \to \infty} \left(\sum_{k=1}^{n} \psi(x^{(n)})\right) \overset{\psi \text{ is linear }}{=} \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} x_k \psi(e^{(k)})\\ & = \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} x_k y_k = \left[\Psi_p(y)\right](x). \end{align*}\]Now it remains to show that $y \in \ell^q$. Define $y^{(n)}=\left(y_1, \ldots, y_n, 0,0, \ldots,\right)$ and $x^{(n)}$ as

\[x_k^{(n)}= \begin{cases} \left|y_k^{(n)}\right|^{q-1} \frac{\overline{y_k^{(n)}}}{\left|y_k^{(n)}\right|}, & y^{(n)}_k \neq 0,\\ 0, & y^{(n)}_k = 0. \end{cases}\]Since $q$ and $p$ are conjugate parameters, we have $(q-1) p=q$. So $\forall k, \left|x^{(n)}_k\right|^p=\left|y^{(n)}_k\right|^q,||x^{(n)}||_p^p=||y^{(n)}||_q^q$ and $x^{(n)} \in \ell^p$ ($x^{(n)}$ is a truncated sequence so this is obvious even without the previous equalities). Futhermore,

\[\begin{equation} \left\|y^{(n)}\right\|_q^q=\sum_{k=1}^n\left|y_k\right|^q \overset{\dagger}{=} \left|\psi(x^{(n)})\right| \leq \|\psi\|\left\|x^{(n)}\right\|_p \leq c\|\psi\| \tag{$*$} \end{equation}\]for some $c \in \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0}$.

$\dagger$ is because

\[\begin{aligned} \left|\psi(x^{(n)})\right| &= \left| \psi(\sum_{k=1}^n x_k^{(n)}e^{(k)}) \right| = \left| \sum_{k=1}^n x_k^{(n)}\psi(e^{(k)}) \right| = \left| \sum_{k=1}^n x_k^{(n)}y^{(n)}_k \right| = \left| \sum_{k=1}^n \left|y_k^{(n)}\right|^{q-2} \overline{y_k^{(n)}} y_k^{(n)}\right|\\ &= \sum_{k=1}^n \left| y_k^{(n)} \right|^q = \sum_{k=1}^n \left| y_k \right|^q. \end{aligned}\]Passing to the limit $n \to \infty$ in gives $||y||_q \leq c|\psi| < \infty$ and hence $y \in \ell^q$. This completes the proof of surjectivity. ◼

Theorem 2 (Riesz’s $\ell^p$ representation theorem $p = \infty$) Let $c_0$ be the closed subspace of $\ell^{\infty}$ consisting of sequences convergent to 0. Define $\Psi_{\infty}: \ell^1 \to (c_0)^*$ as

\[\left[\Psi_{\infty}(y)\right](x)=\sum_{k=1}^{\infty} x_k y_k .\]Then $\Psi_{\infty}$ is an isomorphism.

Proof: $\forall y \in \ell^1$, define $\Psi(y) \in (c_0)^*$ as the restriction of $\Psi _{\infty}(y)$ to ${c}_0$, i.e. $\forall x \in {c}_0$ we set $\Psi(y)(x)=\Psi _{\infty}(y)(x)$.

$\Psi(y)$ is linear:Obvious (in the sense that we have done a similar one).

$\Psi$ is norm preserving:Let $y \in \ell^1$ and $x \in {c}_0$. By triangle inequality and Hölder’s inequality, we have

\[|\Psi(y)(x)| \leq \sum_{k=1}^{\infty}\left|x_k y_k\right| \leq\|y\|_1\|x\|_{\infty},\]so that $\ \lVert \Psi(y) \rVert \leq \lVert y \rVert _1$. Note that this shows that $\Psi(y)$ is bounded and $\Psi$ is well defined. To see that $\ \lVert \Psi(y) \rVert = \lVert y \rVert _1$, define the sequence $x^{(n)} \neq 0$ as ($x^{(n)} = 0$ is not a problem - check this!)

\[\tag{$\dagger$} x_k^{(n)}= \begin{cases}0, & \text { if } y_k=0 \text { or } k>n, \\ \frac{\overline{y_k}}{\left|y_k\right|}, & \text { if } y_k \neq 0.\end{cases}\]Since $ \lVert x^{(n)} \rVert _{\infty}= 1$, we have

\[\frac{\Psi(y)\left(x^{(n)}\right)}{\|x^{(n)}\|_{\infty}}=\sum_{k=1}^n\left|y_k\right| \overset{n \rightarrow \infty}{\rightarrow}\|y\|_1.\]Note that the supremum in this case cannot be attained (If an upper bound, in this case $\lVert y \rVert _1 \lVert x^{(n)} \rVert _{\infty}$, of a set can be approached by a sequence in that set, then this upper bound is a supremum). This is quite different from the case for $p < \infty$ because for $p < \infty$ we can find a sequence $x$ such that the equality holds (i.e. supremum is in fact the maximum).

$\Psi$ is linear:Obvious (in the sense that we have done a similar one).

$\Psi$ is surjective:We now show that any linear functional on $c_0$ can be obtained in this way i.e. $\forall \psi \in (c_0)^* ~ \exists y \in \ell^1$ such that $\Psi(y) = \psi$. Define the sequence $(e^{(n)}) \subset c_{00}$ as

\[e_k^{(n)}= \begin{cases}1 & \text { if } n=k \\ 0 & \text { otherwise. }\end{cases}\] Claim:$\forall x \in {c}_0$, we have

\[x=\sum_{k=1}^{\infty} x_k e^{(k)}.\] Proof of the claim:Let \(x^{(n)}=\sum_{k=1}^n x_k e^{(k)}.\) Observe that \(\left\|x-x^{(n)}\right\|_{\infty} = \|(0,\dots, 0, x_{n+1}, x_{n+2}, \dots, x_{m}, \dots)\|_{\infty} = \sup_{k \geq n+1}|x_n| \overset{n \to \infty}{\to} 0\)

since $x_n \to 0$. So $x^{(n)} \to x$ as claimed. ◼

Note that this claim is not true if we replace ${c}_0$ with $\ell^{\infty}$ as we no longer have $x_n \to 0$.

For $\psi \in ({c}_0)^*$, define the sequence $y$ as $y_k = \psi(e^{(k)})$. We can see that if $y \in \ell^{1}$ (check later), then $\forall x \in {c}_0$,

\[\begin{align*} \psi(x) &= \psi \left(\lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{k=1}^{n} x^{(n)}\right) \overset{\psi \text{ is bounded }}{=} \lim_{n \to \infty}\psi \left(\sum_{k=1}^{n} x^{(n)}\right) \overset{\psi \text{ is linear }}{=} \lim_{n \to \infty} \left(\sum_{k=1}^{n} \psi(x^{(n)})\right) \overset{\psi \text{ is linear }}{=} \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} x_k \psi(e^{(k)})\\ & = \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} x_k y_k = \left[\Psi_p(y)\right](x). \end{align*}\]Now it remains to show that $y \in \ell^1$.

Indeed, for $x^{(n)}$ defined as in $(\dagger)$, we have \(\sum_{k=1}^n\left|y_k\right|=\psi\left(x^{(n)}\right) \leq\|\psi\|\left\|x^{(n)}\right\| \leq\|\psi\| .\) Passing to the limit $n \rightarrow \infty$ gives $\lVert y \rVert _1 \leq \lVert \psi \rVert <\infty$. This completes the proof of surjectivity. ◼

Exercises

Later when I feel particularly productive.